Base Architecture

The app follows the base idea of MVVM, adhering to the official Flutter architecture guideline. However, some adjustments are established in terms of terminology, further explained in this page. We also provide a few samples on how to follow our guidelines in order to establish new or extend existing features of the app.

MVVM Adaption

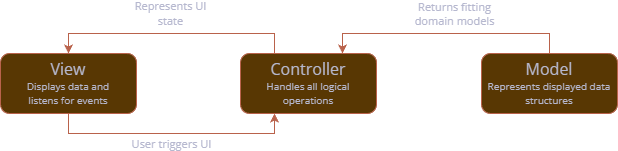

MVVM is adapted by using the term of controllers for the centralized logical unit instead of view model. The relation is as follows and also expressed by the diagram below:

The view is the visual element accessed by the user, therefore representing the actual screen which is accessed within the app. It should not contain any complex logic (exceptions are conditional renderings of images or animations). Interacting with the screen may trigger operations within the controller.

The controller (in context of MVVM: the view model) accepts incoming triggers of the UI and handles logical operations internally. It is responsible for notifying the UI when changes that need to be rendered happen and hosts all operations to load model data.

Models define data structures which need to be represented within the UI. This can be complex data models fetched by an API service or just some primitive data types needed for the current screen. For the latter, it is not always needed to put models into separate classes. Instead, variables may just be established and maintained within the controller itself.[

MVVM Implementation in Flutter

Controllers are based on the class ChangeNotifier which is used to notify interested entities of updates by calling the method notifyListeners(). In other words, the ChangeNotifier might do internal operations which are triggered by data providers or the user within the view and calls notifyListeners() whenever something happens that would update a UI element within the view. A sample is given below: Fields should be private and only exposed using custom properties or methods. Changing a field in this exemplary CounterController would result in a notification because the number has been updated.

Views are represented through widgets, which should depend on ChangeNotifiers if they should update through their logic. As the notifier itself is able to re-trigger Flutter's build() method, the Widget can be created stateless, no matter that its content should change during runtime. In order for the Widget to subscribe to changes of the ChangeNotifier, it should call context.watch<T>() where T stands for the relevant controller type. Not only can controller variables and methods be accessed, but the Widget will also automatically update, as the following example using the controller from above illustrates:

Lastly, watching the ChangeNotifier can only work if it is injected higher up in the widget tree, usually utilizing a ChangeNotifierProvider like so:

BaseController and BaseControllerBuilder

To simplify operations that we need in almost every controller (namely, loading status and possible error cases), class BaseController was created. This abstract class is used by most existing controllers and extends ChangeNotifier. It stores a state variable for whether the controller is currently loading data (isLoading) and a nullable error text (error) which should be null when there is no error. Both states can be set using corresponding methods setIsLoading or setError.

To simplify rendering process of BaseControllers, a utility Widget class BaseControllerBuilder was established. This builder needs the controller instance and a callback builder which is only called once the controller has no loading or error state.

Constructing Models

Models may be established through separate data classes which store relevant data. Model classes should be immutable, establishing the need to create a new instance when the model is altered. This is usually done by offering a copyWith() implementation. The following sample shows a model class for the counter implementation established earlier:

When having a class model, implementation in the controller shifts as well. For the given example, the updated CounterController could look like this:

Data Models for Data Sources and Domain Models

Besides data models which just represent internal data logic, it often boils down to models which mimic data returned by some kind of data source which could be APIs as well as local files or databases. Our recommended best practice is to always separate a domain model (therefore, the model just containing data) from possible data source models (models which represent a domain-ish data structure).

To give an example, imagine there is a JSON API which returns a response like this:

Our goal now is to first wrap data in a domain model, which could look like this:

This model now gets a data source representation for the JSON API. Such representations usually reflect the very same model base structure, however usually adapting utilities to construct the model instance (in this case, a factory constructor loading the model from JSON). Moreover, the data source model should contain a method which returns the domain model representation of the very same model (in the following sample, this is done through toDomain()).

Having both model implementations, fetching API data and turning them into the domain model is a piece of cake and could easily be supplemented by any other implementation, such as a local storage loading operation:

Loading Data through Repositories

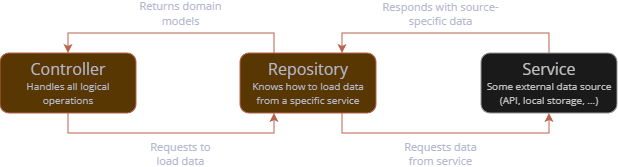

As app complexity grows and multiple data sources could be involved to get a final model domain representation, the need for a separate data fetching layer arises. This is done through so-called repositories which are basically just ways that define how models are loaded from a specific data source.

Unidirectional data flow which is established through a controller "asking" for data is shown in the following figure:

Before we look into specific repository types covered in the app, let's start with the basics. A repository should always depend on an abstract class which defines methods the repository covers.

Repository methods should always have a return type of Future<Result<T>> where T represents the type of domain model the repository request returns.

While Dart-builtin Future stands for an asynchronous operation, the type Result is project-specific and plays a crucial role. A Result reflects the fact that each repository request can have one of two outcomes: It can either succeed (meaning the request was successful and provides data) or fail (meaning there was a non-positive outcome and an error was set within the Result). We will shortly cover utility that can be used to handle both possible outcomes efficiently.

An exemplary abstract repository class using the named aspects to get a lsit of the Human domain model defined above could look like this:

Using repositories concludes the base structure most controllers in the app use: Usually an initialization method loads all required repository data. Therefore, utility method when of the Result class can be used, having two important optional callbacks:

success: Reflects a successful response and provides the object returned.failure: Called when the request failed, providing the errorStringas a parameter.

Within an exemplary controller, this could be used as follows for a single repository:

When instantiating the controller, not only some concrete repository implementation has to be injected (here, with an example introduced later), but also the method initialize() should be called so data is loaded once the controller is accessed for the very first time:

API Repositories

Most repositories rely on API request. Therefore, two base classes come into play:

ApiClient: Represents some client which is used to perform the requestsClientRepository: Base class for repositories that perform API requests.

An API repository should extend ClientRepository while some APIClient is injected into the class. The request itself is wrapped within the method guardRequest() which is provided by ClientRepository. This method makes sure to correctly handle error cases occurring during the request or in data parsing operations. The following sample shows how some (imagined) endpoint could be used to load a list of the exemplary Human domain model, using the data source model shown earlier.

Local Repositories

Local repositories are primarily used to save local settings. Therefore, they often reflect a pattern with a separate load and set method. Let's imagine a use-case where we need settings to save and load a username. The base repository could look like this:

Local repositories should extend the utility base class LocalRepository which uses GetStorage under the hood to handle local saving and loading operations. For the given primitive data type String, we can use the simple method implementations readValue() and writeValue() like so, while relying on an injected GetStorage instance and a specific key under which data is saved:

The shown primitive methods are able to handle numeric data, boolean values and Strings. For more complex types there are additional utility methods:

readValueAsListto read a list (the list itself can be saved using thewriteValue()method already shown for primitive data types)readEnumandwriteEnumfor enum valuesreadEnumListandwriteEnumListfor enum list values

Injection for the GetStorage instance is easy as can be in the BootLoader through the created variable getStorage:

Hive Repositories

In some cases, it could be needed to serialize entire data class structured. In such cases, using GetStorage to serialize each variable or the entire object using a JSON representation is not only kind of overkill, but also computation-heavy. Instead, we use Hive CE, a lightweight database.

Imagine that we want to have a use-case to create, save and load our very own Human model data, established earlier. For Hive, a separate data source model is created. The class itself must provide @HiveType annotation with a project-unique typeId. We incrementally assign this ID, so please be aware to look up the lately added model and increment its type ID by 1. In the class, each field has a @HiveField annotation, with an incremental value as well (however, this value only has to be unique within the class itself). Moreover, as we mostly need some way to get the Hive representation from domain model, Hive model classes usually need a fromDomain() constructor. Lastly, in order for automatic generation of boilerplate classes to work, a part annotation should be added above the class, representing a fitting class name.

An example for the Human Hive representation could be as follows:

Next up, we could imagine a repository used to load and save Humans. For testability, such repositories should have the optional possibility to inject a HiveInterface which sould default to Hive if not set (mocked) otherwise. Data is saved and loaded through a so called box referenced by a specific key. The key should be set in a constant as we will need it for registration later. While not showing the base class for simplicity, the Hive repository implementation could look like this:

In order for Hive to generate boilerplate code for the data model, the new model has to be registered. This is currently done in main.dart as follows, using the same box name as in the repository itself:

In order for all examples to work, finally generate Hive boilerplate code using the following command within the project root: